Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating

Introduction

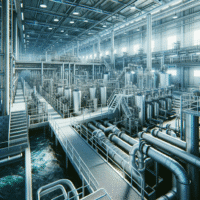

In municipal wastewater treatment and industrial sludge handling, the premature failure of progressive cavity (PC) pump stators remains one of the most persistent and costly maintenance burdens. Engineers frequently specify robust hydraulic conditions, yet the interface between the pump mechanics and the electrical control system is often where reliability disintegrates. A startling volume of stator failures—often categorized as “wear”—are actually thermal events caused by improper integration. Specifically, the nuances of Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating are frequently overlooked during the submittal review and commissioning phases, leading to catastrophic elastomer failure within months of installation.

Progressive cavity pumps operate on the principle of an interference fit between a metallic rotor and an elastomeric stator. This interference is necessary to create the sealed cavities that move fluid, but it inherently generates friction. In typical applications such as Return Activated Sludge (RAS), Waste Activated Sludge (WAS), dewatered cake transfer, and polymer dosing, the pumped fluid acts as both a lubricant and a coolant. When the Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) is not programmed to respect the thermodynamic and mechanical limits of this interference fit, heat accumulates rapidly. This can result in two distinct failure modes: the “melted” stator caused by running dry, or the more insidious “hysteresis cracking” caused by operating at speeds or pressures that generate internal heat faster than the elastomer can dissipate it.

For consulting engineers and plant superintendents, understanding the critical relationship between VFD parameters (such as carrier frequency, minimum hertz, and torque boost) and the physical pump characteristics is mandatory. A standard “fan and pump” VFD setup will fail a PC pump. This article provides a deep technical dive into the engineering specifications, control logic, and operational strategies required to ensure lifecycle reliability, focusing specifically on how correct drive configuration prevents thermal destruction.

How to Select and Specify for Thermal Protection

Preventing overheating begins long before the VFD parameters are keyed in; it starts with the equipment specification. The selection process must account for the unique thermal properties of the elastomer and the motor cooling limitations under high-turndown scenarios. Below are the engineering criteria required to optimize Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating.

Duty Conditions & Operating Envelope

The operating envelope of a PC pump is defined not just by flow and head, but by the thermal interaction between the fluid and the stator. Engineers must evaluate the following:

- Fluid Temperature vs. Stator Rating: Standard nitrile stators may be rated for 160°F (71°C), but this rating assumes the fluid is the only heat source. In operation, friction adds 20°F to 40°F (11°C to 22°C) at the interface. If the process fluid is 140°F, the interface temperature may exceed the elastomer’s limit, causing swelling, increased friction, and thermal runaway.

- Viscosity and Friction: Highly viscous fluids (dewatered sludge, cake) generate significant shear heat. The VFD specification must allow for “Constant Torque” operation. Unlike centrifugal pumps where load drops with the cube of speed, PC pumps require constant torque throughout the speed range. Specifying a “Variable Torque” (VT) drive is a critical error that leads to motor overheating at low speeds.

- Turndown Ratio Limits: A 10:1 turndown is common, but running a standard TEFC (Totally Enclosed Fan Cooled) motor at 6 Hz (10% speed) provides almost no cooling airflow from the shaft-mounted fan. The specification must require an electric auxiliary cooling fan (blower cooled) for the motor if continuous operation below 20-25 Hz is anticipated.

Materials & Compatibility

The material selection directly influences the thermal resilience of the system. The Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) of rubber is roughly 10 times that of steel. As heat builds up—whether from the fluid or friction—the stator swells inward, gripping the rotor tighter. This increases torque demand and friction, creating a positive feedback loop of heat generation.

- Elastomer Selection: For high-temperature or high-friction applications, engineers should specify Fluoroelastomers (FKM/Viton) or Hydrogenated Nitrile (HNBR) which offer higher thermal ceilings than standard NBR.

- Interference Sizing: In applications known for heat risk, specifying a “loose fit” or “high-temperature fit” rotor/stator combination allows for thermal expansion without seizing. However, this reduces volumetric efficiency at low viscosities, so the VFD must be tuned to compensate for slip.

Hydraulics & Process Performance

Process constraints often dictate VFD settings that inadvertently cause overheating.

- Slip and Heat: “Slip” is the fluid that leaks back across the sealing line from high pressure to low pressure. Slip generates shear heat. If a VFD is set to run the pump too slowly against high backpressure, the percentage of slip increases. If slip exceeds ~20-30%, the fluid recirculating within the cavities heats up rapidly. The VFD minimum speed (Min Hz) must be set above the point where significant slip occurs.

- NPSH and Cavitation: Operating a PC pump with insufficient Net Positive Suction Head (NPSH) causes cavitation. While usually associated with pitting, the collapsing vapor bubbles also generate localized hot spots and interrupt the lubricating film between rotor and stator, leading to rapid frictional heating.

Installation Environment & Constructability

The physical environment impacts the VFD’s ability to manage heat.

- VFD Cable Length: Long cable runs (>100 ft) between the VFD and the motor can cause voltage spikes (dV/dt) that overheat the motor windings. While this heats the motor rather than the stator, the result is system failure. Engineers must specify load reactors or dV/dt filters for long runs.

- Ambient Temperature: If the pump is installed in a hot, non-ventilated room, the baseline temperature of the stator is already elevated. The VFD enclosure must also be rated for the environment to prevent drive derating or tripping.

Reliability, Redundancy & Failure Modes

To achieve a robust Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating, redundancy in sensing is required.

- Run-Dry Protection: The most critical failure mode. Relying solely on motor under-current (low amp) detection is often insufficient for PC pumps because the starting torque and running friction can mask a dry-run condition until damage is done.

- Recommended Sensors:

- Stator Thermistors: Sensors embedded directly into the elastomer stator wall. They provide the fastest response to friction heat.

- Flow/Pressure Switches: A suction side pressure switch or discharge flow switch provides a secondary confirmation of fluid movement.

Controls & Automation Interfaces

The specification must define how the VFD interacts with these sensors.

- Hardwired Interlocks: Thermal protection (stator thermistors) should be hardwired to the VFD’s safety circuit or a dedicated relay, not just an analog input to SCADA. SCADA lag time is often too slow to save a stator.

- Torque Monitoring: Modern VFDs can monitor torque output. A sudden spike in torque (without a speed change) often indicates stator swelling (overheating). A sudden drop indicates a line break or run-dry. The VFD should be programmed with “Window” alarms for torque.

Lifecycle Cost Drivers

The cost of a stator replacement includes the part ($500-$5,000), labor (4-8 hours), and process downtime. Investing in a premium VFD with direct thermal sensor inputs and specifying the embedded sensors in the pump adds roughly 5-10% to the initial capital cost but can eliminate 80% of premature failures. The ROI on thermal protection is typically less than one failure event.

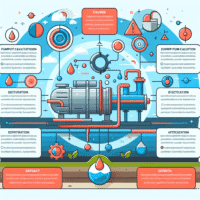

Comparison of Thermal Protection Strategies

The following tables provide a comparative analysis of methods used to protect progressive cavity pumps from thermal damage. Engineers should use these matrices to select the appropriate level of protection based on application criticality.

Table 1: Thermal Protection Technologies for PC Pumps

| Technology/Method | Primary Mechanism | Best-Fit Applications | Limitations/Risks | Typical Maint. Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embedded Stator Thermistor (RTD/PTC) | Direct temperature measurement of the elastomer interface. | Critical sludge transfer, polymer dosing, high-solids cake pumps. | Requires specific stator manufacturing; replacement stators must have ports. sensor wiring is fragile. | Check continuity during stator changes; recalibrate controller annually. |

| VFD Power/Torque Monitoring | Algorithms detect load loss (run dry) or load spike (swelling). | General wastewater transfer, non-critical applications. | Indirect measurement; false trips common with varying viscosity; may not catch dry run fast enough. | Software only; requires tuning during commissioning. |

| Suction/Discharge Pressure Switches | Detects loss of suction pressure or lack of discharge pressure. | Clean water, thin sludge, applications with consistent supply. | Diaphragms can clog in thick sludge (ragging); slow response time compared to thermistors. | Monthly cleaning of isolation rings/diaphragms required. |

| Flow Switch (Thermal Dispersion/Magnetic) | Verifies actual fluid movement. | Chemical metering, polymer, critical dosing. | Intrusive probes can foul; non-intrusive (mag) are expensive for large pipes. | Regular cleaning of probe tips. |

| Acoustic / Vibration Monitoring | Listens for cavitation or dry-running mechanical noise. | Large, high-capital pumps in remote stations. | High cost; complex setup; often overkill for standard municipal pumps. | Periodic sensor calibration. |

Table 2: Application Fit Matrix for VFD Control Strategies

| Application Scenario | Recommended VFD Mode | Min. Hz Setting (Typical) | Thermal Risk Level | Required Accessory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thin Sludge (WAS/RAS) < 2% Solids | Sensorless Vector / Constant Torque | 15-20 Hz | Medium | Stator Thermistor or Dry Run Switch |

| Thick Sludge / Cake > 6% Solids | Closed Loop Vector (w/ Encoder) or Direct Torque Control | 5-10 Hz | High (Friction) | Motor Blower Cooling + Stator Thermistor |

| Polymer Dosing (Clean, Viscous) | Volts/Hz or Sensorless Vector | 10 Hz | High (Run Dry) | Flow Verification Switch |

| Variable Viscosity (Digester Feed) | Constant Torque w/ Torque Limiting | 20 Hz | Medium | Torque Monitoring Alarms |

Engineer & Operator Field Notes

Successful implementation requires bridging the gap between the design office and the pump room floor. The following field notes address practical aspects of Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating during commissioning and daily operations.

Commissioning & Acceptance Testing

The most dangerous moment in a PC pump’s life is the first startup. Contractors often want to “bump” the motor to check rotation.

During the Site Acceptance Test (SAT), the engineer must verify the VFD parameters:

- Base Frequency Voltage: Ensure the VFD is providing full voltage at the motor’s nameplate frequency.

- Carrier Frequency: Check the carrier frequency (switching frequency). High carrier frequencies (e.g., 8-12 kHz) reduce audible motor noise but increase heat in the VFD and can cause voltage standing waves that damage motor insulation. For PC pumps, a lower carrier frequency (2-4 kHz) is often preferred to maximize drive thermal capacity, provided audible noise is acceptable.

- Thermal Trip Test: If stator sensors are installed, physically disconnect the sensor wire to verify the VFD trips on “Sensor Fault” or simulates an over-temp condition. Do not assume the logic works.

Common Specification Mistakes

One frequent error in RFP documents is copying centrifugal pump VFD specs for PC pumps. Centrifugal pumps use “Variable Torque” loads (torque varies with speed squared). PC pumps are “Constant Torque” loads. Specifying a “Normal Duty” or “Variable Torque” rated VFD usually results in a drive that is undersized for the starting torque requirements of a PC pump, leading to drive overheating or failure to start (which heats the motor windings).

O&M Burden & Strategy

Operational strategy plays a role in thermal management. Operators should be trained to recognize that “increasing speed” does not always equal “more flow” if the stator is worn. As the stator wears, slip increases. Increasing speed to compensate generates more friction heat. Eventually, the thermal limit is reached, and the stator chunks out.

Recommended Maintenance Checks:

- Weekly: Check VFD display for average amperage. A gradual rise in amperage at a constant speed suggests stator swelling (early overheating warning).

- Monthly: Verify cooling fan operation on the motor. A blocked fan cowl is a leading cause of motor overheating.

- Quarterly: If TSPs (Thermal Stator Protectors) are used, check resistance values against the manufacturer’s baseline.

Troubleshooting Guide: The “Hot Pump” Scenario

If a PC pump is found running hot:

- Check Discharge Pressure: Is the line plugged? High pressure equals high torque and high friction.

- Check Suction: Is the pump starved? Cavitation sounds like marbles in the pipe; dry running is often silent until the squealing starts.

- Check VFD Speed: Is the pump running at 5 Hz? Without an auxiliary fan, the motor cannot cool itself. The heat from the motor shaft can conduct into the rotor/stator assembly.

- Check Bolting: Overtightened tie rods (on certain designs) can compress the stator longitudinally, increasing the interference fit and friction.

Design Details: Sizing and Configuration

This section outlines the specific calculations and logic required to ensure the Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating is engineered correctly.

Sizing Logic & Methodology

Sizing the VFD for thermal safety requires satisfying the “Break-Away Torque.” PC pumps have a high static friction (stiction) due to the interference fit. The VFD must be able to provide 150% to 200% of nominal torque for a short duration to start the pump.

Sizing Rule of Thumb:

For Constant Torque loads like PC pumps, always select a VFD rated for “Heavy Duty” or “Constant Torque” service. Often, this means upsizing the drive by one HP size relative to the motor if the motor is near the top of the drive’s amperage rating.

Calculating Heat Generation (simplified):

Heat (Q) generated in the stator is a function of friction and hysteresis.

Q ∝ (Speed × Interference Fit × Viscosity Factor)

While exact calculation requires proprietary manufacturer data, the relationship shows that doubling the speed significantly increases heat load. Therefore, conservative design dictates selecting a larger pump running at slower speeds (e.g., 200 RPM) rather than a smaller pump running fast (e.g., 400 RPM) for viscous sludge, purely to manage thermal load.

Specification Checklist

To ensure a robust system, include these items in the Division 11 or Division 43 specifications:

- Motor: Inverter Duty rated per NEMA MG1 Part 31. Insulation Class F or H. Service Factor 1.15 (though usually 1.0 on VFD).

- Auxiliary Cooling: Mandatory constant-speed blower for the motor if operation below 20 Hz is permitted.

- VFD Mode: Specified as “Constant Torque” or “Vector Control.”

- Protection: “Pump shall be equipped with stator temperature probes wired to the VFD to trip the unit upon high temperature detection.”

- Starting Ramp: “VFD shall be programmed with a starting ramp not exceeding 5-10 seconds to ensure break-away, followed by a controlled process ramp.” (Too slow of a start ramp can keep the motor in high-current/locked-rotor state too long).

Standards & Compliance

Adherence to standards ensures safety and interoperability:

- NEMA MG1 Part 31: Defines the insulation requirements for motors operated on VFDs to withstand voltage spikes without overheating or insulation breakdown.

- NFPA 70 (NEC): Article 430 covers motor circuits. Thermal protection (overload) is required. Note that standard bi-metallic overloads may not trip fast enough to save a stator; electronic protection inside the VFD is superior.

- AWWA Standards: While AWWA has pump standards, specific thermal protection protocols for PC pumps are often found in manufacturer best practices rather than a unified AWWA standard, making the engineer’s spec crucial.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the minimum safe speed for a progressive cavity pump on a VFD?

The minimum safe speed depends on the motor cooling method and the pump’s slip characteristics. For the motor, a standard TEFC motor should generally not run below 20-25 Hz continuously without auxiliary cooling. For the pump hydraulics, the minimum speed must be high enough to overcome slip (internal backflow). If slip is excessive, the fluid recirculates and overheats. A typical safe minimum is often 10-15 Hz, but this must be verified against the specific pump curve and discharge pressure.

Why is “Constant Torque” setup required for Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating?

PC pumps displace a fixed volume per revolution regardless of speed, and the torque required to turn the rotor is determined by the interference fit and the discharge pressure. This torque demand remains high even at low speeds. If a VFD is set to “Variable Torque” (like a fan), it reduces voltage (and torque capacity) at low speeds to save energy. This will cause the motor to stall, draw excessive current, and overheat the windings while failing to turn the pump.

How do stator temperature probes work?

Stator temperature probes are typically Thermistors (PTC) or RTDs inserted into a drilled hole in the stator’s metal shell, reaching close to the elastomer interface. They measure the temperature of the rubber. The VFD or a separate relay monitors the resistance. If the temperature exceeds a setpoint (e.g., 140°F or 60°C), the circuit opens, tripping the pump to prevent the rubber from melting or chunking out.

Can I use a VFD current limit to prevent run-dry?

It is difficult and often unreliable. While running dry does reduce the load (amperage), the high friction of the interference fit means the pump still draws significant power even when empty. The difference between “running with fluid” and “running dry” might be too small for a standard VFD under-load setting to detect reliably before the stator burns. Stator temperature probes or flow switches are far more reliable.

What causes hysteresis heating in PC pump stators?

Hysteresis heating occurs when the rubber stator is repeatedly compressed and released by the passing rotor lobes. This internal flexing generates heat within the rubber material itself (similar to bending a paperclip back and forth). If the pump runs too fast or the pressure is too high, this internal heat cannot dissipate into the fluid or the metal housing fast enough, causing the rubber to degrade from the inside out. Proper sizing limits the speed to prevent this.

How does VFD carrier frequency affect motor overheating?

The carrier frequency is the rate at which the VFD’s IGBTs switch voltage. Higher carrier frequencies (e.g., 8-16 kHz) create a smoother wave and reduce audible noise, but they generate more heat in the VFD and can create higher voltage spikes (dV/dt) at the motor terminals. For industrial wastewater applications, a lower carrier frequency (2-4 kHz) is often recommended to reduce thermal stress on the VFD and improve overall system efficiency, provided the audible whine is acceptable.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Torque Mode is Critical: Always configure VFDs for Constant Torque / Heavy Duty operation. Variable torque settings will cause low-speed stalls and motor overheating.

- Sensor Integration: Do not rely on current monitoring alone. Specify embedded stator thermistors or reliable flow switches to prevent dry-run burnout.

- Auxiliary Cooling: For operations below 20 Hz, standard TEFC motors are insufficient. Specify blower-cooled motors to protect the windings.

- Sizing for Heat: Oversize the pump to run at lower speeds (200-300 RPM max) for abrasive or viscous sludge to minimize frictional heat and hysteresis.

- Interference Fit: Match the elastomer and rotor dimension to the temperature. High-temp fluids require loose-fit rotors or specialized elastomers.

- Start-Up Protocol: Never dry-bump a PC pump. Ensure the spec requires priming before the first rotation.

The reliability of a sludge handling system hinges on the correct execution of the Progressive Cavity VFD Setup: Preventing Overheating. While the mechanical selection of the pump frames the potential for success, the electrical integration dictates the reality of the lifecycle. By moving beyond basic speed control and embracing a holistic view of thermal management—incorporating stator sensors, proper motor cooling, and constant-torque VFD logic—engineers can virtually eliminate the most common cause of PC pump failure.

Specifications should be viewed as a system design rather than a collection of components. The cost of adding thermal probes and auxiliary fans is negligible compared to the operational expenditure of replacing a burned stator and the associated downtime. For the municipal engineer and the plant superintendent, the path to reliability lies in recognizing that a progressive cavity pump is a friction machine first, and a fluid mover second; managing that friction is the key to longevity.