Westfall Manufacturing vs SPX Lightnin for Mixers: Pros/Cons & Best-Fit Applications

Introduction

In the design of water and wastewater treatment facilities, the rapid and uniform dispersion of chemicals—coagulants, disinfectants, and neutralizing agents—is a fundamental determinant of process efficiency. A surprising statistic in the municipal sector indicates that up to 30% of chemical costs are wasted due to inefficient mixing, leading to overdosing to achieve regulatory compliance. For engineers and plant directors, the choice of mixing technology is not merely a component selection; it is a critical control point that dictates operational expenditure (OPEX) for the life of the facility.

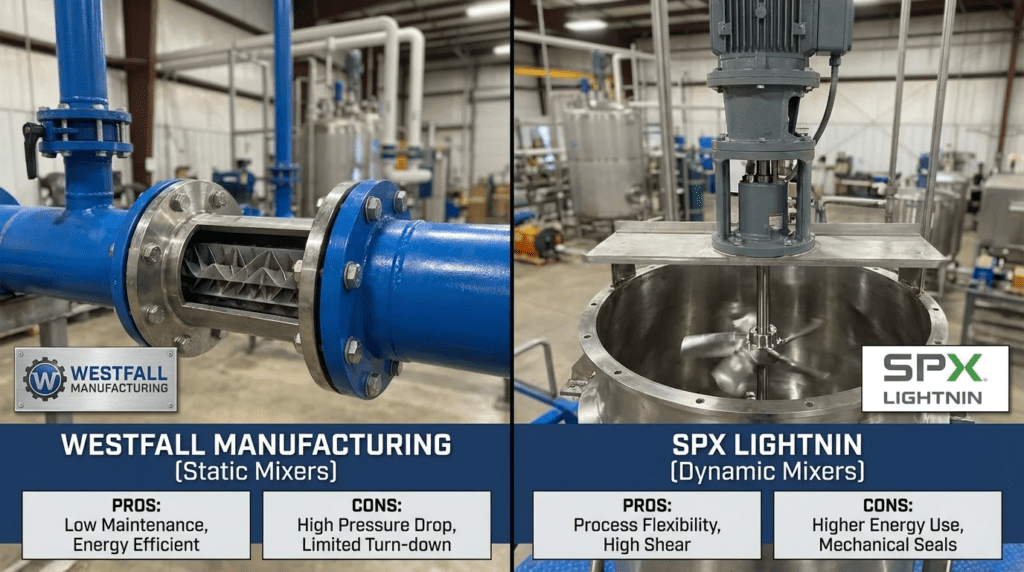

When evaluating market leaders, engineers frequently encounter a strategic decision regarding Westfall Manufacturing vs SPX Lightnin for Mixers: Pros/Cons & Best-Fit Applications. This comparison is rarely a straightforward “apples-to-apples” evaluation of two similar machines. Instead, it represents a choice between two distinct engineering philosophies: the high-efficiency static (motionless) mixing approach championed by Westfall Manufacturing, and the robust dynamic (mechanical) mixing approach exemplified by SPX Lightnin.

These technologies find their homes in critical unit processes such as flash mixing, flocculation, chlorination, and dechlorination. However, the operating environments differ significantly. Westfall’s static solutions are predominant in space-constrained pipeline applications where head loss management is paramount. Conversely, SPX Lightnin’s dynamic mixers dominate open basins, solids suspension applications, and scenarios where flow variability (turndown) renders static mixing ineffective. A poor specification here can lead to disastrous consequences: insufficient G-values (velocity gradients), short-circuiting, massive energy penalties from unnecessary head loss, or mechanical failures in harsh environments.

This article provides a rigorous, engineer-to-engineer analysis of these two approaches. It moves beyond catalog data to explore the fluid mechanics, reliability profiles, and total cost of ownership (TCO) inherent in selecting between static and dynamic mixing strategies for municipal and industrial applications.

How to Select / Specify

Selecting the correct mixing technology requires a holistic review of the hydraulic profile, process chemistry, and physical constraints of the plant. Below are the critical engineering criteria when evaluating Westfall Manufacturing vs SPX Lightnin for Mixers: Pros/Cons & Best-Fit Applications.

Duty Conditions & Operating Envelope

The primary differentiator between these technologies is their response to flow variation. Static mixers (Westfall) derive their mixing energy entirely from the fluid’s momentum. Therefore, their performance is intrinsically linked to flow velocity.

- Flow Turndown: Engineers must evaluate minimum, average, and peak flows. If the plant experiences high turndown ratios (e.g., > 3:1 or 4:1), a static mixer may fail to generate sufficient turbulence at low flows, resulting in a poor Coefficient of Variation (CoV). In contrast, SPX Lightnin dynamic mixers apply external energy via a motor and impeller, maintaining constant mixing intensity regardless of the hydraulic flow rate.

- Reynolds Number: For Westfall static mixers, the Reynolds number must be calculated to ensure turbulent flow (typically Re > 2000-4000 depending on design) is maintained across the operating range.

- Solids Content: For high-solids wastewater or sludge blending, dynamic mixers often perform better as they can prevent settling in tanks. However, specialized non-clogging static mixers exist for sludge lines.

Materials & Compatibility

Water and wastewater streams are aggressive. The material selection must account for both the process fluid and the concentrated chemical being injected.

- Corrosion Resistance: Westfall specializes in fabricating mixers from exotic materials (Titanium, Hastelloy, FRP, and coated 316L SS) to withstand aggressive injection points like sodium hypochlorite or ferric chloride. Since static mixers are often integral to the pipe spool, the liner integrity is critical.

- Abrasion: In grit chambers or raw sewage applications, impeller wear on Lightnin mixers is a maintenance concern. Hardened alloys or rubber-lined impellers are specification options. For static mixers, abrasion can alter the geometry of the mixing vanes over time, changing the head loss characteristics.

- Coatings: For potable water, all wetted parts must be NSF-61/372 certified. Both manufacturers offer compliant solutions, but the application method differs (dip coating/lining for static vs. coating of shafts/impellers for dynamic).

Hydraulics & Process Performance

The energy required for mixing comes from somewhere: either the pump (static) or a dedicated motor (dynamic).

- Head Loss (Static): Westfall Manufacturing is renowned for low-head-loss designs (like the Model 2800). However, all static mixers induce head loss. Engineers must calculate this loss at peak flow and ensure the upstream pumps have sufficient TDH (Total Dynamic Head). The formula $h_L = K cdot (v^2/2g)$ is critical here.

- Power Input (Dynamic): SPX Lightnin mixers consume electrical power continuously. The specification must define the G-value (sec⁻¹) and mixing time (t). Dynamic mixers allow for adjustable G-values via VFDs, offering process control flexibility that static mixers lack.

- Mixing Quality (CoV): The standard specification target is often a CoV of 0.05 (95% homogeneity) at 10 pipe diameters downstream. Westfall mixers achieve this through geometric vane arrangements; Lightnin mixers achieve this through impeller pumping rates and tank turnover calculations.

Installation Environment & Constructability

Space Constraints: This is often the deciding factor.

Westfall (Static): Installed inline, often within a standard pipe spool length. Requires zero footprint capability but demands specific upstream/downstream straight pipe runs to function correctly (typically 1-3 diameters upstream, 3-10 downstream). Ideally suited for retrofits in crowded pipe galleries.

SPX Lightnin (Dynamic): Requires overhead clearance for motor/gearbox removal and structural support (bridges or mounting plates) capable of withstanding torque and bending moments. Not viable for buried pipelines or tight pipe galleries without wet wells.

Reliability, Redundancy & Failure Modes

MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures):

Westfall static mixers have no moving parts. Their MTBF is essentially the life of the pipe material (20-50 years). Failure modes are limited to corrosion, erosion, or catastrophic clogging (ragging).

SPX Lightnin dynamic mixers have mechanical seals, bearings, gearboxes, and motors. While highly reliable (often >100,000 hours L10 bearing life), they have defined failure modes requiring monitoring. Redundancy (N+1) is usually required for dynamic mixers in critical applications, whereas redundancy for static mixers is achieved via parallel pipe trains.

Controls & Automation Interfaces

In modern SCADA-integrated plants, the level of control required dictates the technology.

- Static (Passive): No direct control interface. Mixing energy is purely a function of flow. Chemical dosing pumps must be paced efficiently to match the flow, as the mixer cannot “adjust” its performance.

- Dynamic (Active): Lightnin mixers paired with VFDs offer excellent optimization. During low-flow or low-load periods, impeller speed can be reduced to save energy while maintaining suspension, or increased during shock loading. This requires I/O points for speed reference, running status, and vibration/temp alarms.

Maintainability, Safety & Access

Operator safety and ergonomic access are critical for long-term success.

- Westfall: Maintenance is virtually zero, but inspection is difficult. Inspecting the condition of an inline mixer usually requires shutting down the line and breaking flanges. Access hatches can be specified but add cost.

- SPX Lightnin: Requires routine preventive maintenance (oil changes, greasing). Access to the gearbox on top of a tank can be a fall hazard, requiring platforms and railings. In-tank maintenance (impeller issues) requires confined space entry or crane removal.

Lifecycle Cost Drivers

When analyzing Westfall Manufacturing vs SPX Lightnin for Mixers: Pros/Cons & Best-Fit Applications, the cost structure is inverted.

- CAPEX: Large diameter static mixers can be expensive due to custom fabrication and exotic materials. Dynamic mixers have high costs for motors, drives, and structural supports.

- OPEX: Static mixers have zero direct energy costs, but the “phantom” cost of head loss must be calculated (additional pumping energy). Dynamic mixers have direct electrical costs and ongoing maintenance labor/parts costs. Generally, for continuous high-flow applications, low-head-loss static mixers offer a lower TCO.

Comparison Tables

The following tables provide a structured comparison to assist engineers in quickly delineating the capabilities of static versus dynamic mixing technologies. Table 1 focuses on the technological differences between the two approaches, while Table 2 provides a decision matrix for specific water and wastewater applications.

Table 1: Technology & Manufacturer Comparison

| Feature / Criteria | Westfall Manufacturing (Static/Motionless) | SPX Lightnin (Dynamic/Mechanical) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Utilizes fluid momentum via fixed geometric inserts (vanes/plates) to create turbulence. | Utilizes external energy via motor, gearbox, and rotating impeller to pump fluid. |

| Energy Source | Hydraulic head (pressure drop). | Electrical power (motor). |

| Turndown Capability | Limited. Mixing efficiency drops as velocity decreases (Re number dependency). | Excellent. Can maintain high mixing intensity even at zero throughput flow. |

| Head Loss | Low to Moderate (Model dependent). Engineered specifically to minimize k-value. | Negligible impact on hydraulic profile; adds energy to the system. |

| Maintenance Profile | Near Zero. Periodic inspection for wear/scaling. No moving parts. | Moderate. Oil changes, seal replacements, bearing checks, motor maintenance. |

| Typical Footprint | Inline (Zero footprint). Fits within pipe spool. | Basin/Tank mount or side-entry. Requires structural support and clearance. |

| Primary Limitation | Cannot mix effectively at very low flows; susceptible to clogging with heavy rags. | Higher OPEX (energy + maintenance); mechanical complexity. |

Table 2: Application Fit Matrix

| Application Scenario | Best-Fit Technology | Engineering Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Flash Mixing (Coagulation) | Westfall (Static) | Instantaneous dispersion (< 1 sec) is critical. High turbulence at injection point is achieved more efficiently inline than in large back-mixed tanks. |

| Flocculation Basins | SPX Lightnin (Dynamic) | Requires gentle, controlled energy input (low G-value) and variable speed to build floc without shearing it. Long residence times favor tanks. |

| Chlorination / Dechlorination | Westfall (Static) | Ideally suited for pipe injection. Ensures rapid contact for CT compliance before entering contact basins or discharge. |

| Sludge Holding / Blending | SPX Lightnin (Dynamic) | Solids suspension requires active pumping to prevent settling. Static mixers can clog or fail to suspend solids in large volumes. |

| Chemical Equalization | SPX Lightnin (Dynamic) | Large tanks used to dampen pH or concentration spikes require active turnover, regardless of influent flow rate. |

| Ozone Injection | Westfall (Static) | Sidestream injection with static mixers provides high mass transfer rates for gas-liquid mixing under pressure. |

Engineer & Operator Field Notes

Real-world performance often diverges from catalog curves. The following observations are drawn from field experience in commissioning and operating both Westfall and Lightnin systems.

Commissioning & Acceptance Testing

Westfall (Static):

Commissioning a static mixer is largely a verification of the hydraulic profile.

Field Test: Inject a tracer (dye or salt) upstream and measure concentration at the specified downstream distance (e.g., 10D). Calculate the CoV.

Checkpoint: Verify that the pressure drop across the mixer matches the submittal curve. High pressure drop may indicate blockage or construction debris; low pressure drop may indicate insufficient flow for design mixing.

SPX Lightnin (Dynamic):

Commissioning involves mechanical and electrical verification.

Field Test: Vibration analysis (baseline signature) is mandatory. Check motor amperage draw against the prop curve to ensure the impeller pitch and fluid density match the design.

Checkpoint: Check for “vortexing.” If a vortex reaches the impeller, it causes cavitation and severe mechanical stress. Verify baffle integrity in the tank.

Common Specification Mistakes

Overlooking Turndown in Static Mixers:

A common error is sizing a Westfall mixer for Peak Wet Weather Flow (PWWF) and ignoring the Average Dry Weather Flow (ADWF). If the velocity at ADWF is too low, the mixer becomes a passive obstruction rather than a turbulence generator.

Solution: Specify a mixer design (like Westfall’s variable beta options or staged injection) that functions across the full hydraulic range, or use parallel trains.

Ignoring Critical Speed in Dynamic Mixers:

For SPX Lightnin units with long shafts (deep tanks), engineers sometimes fail to rigorously check the critical speed (natural frequency) of the shaft. Running a mixer near its critical speed guarantees resonant vibration and failure.

Solution: Specify that the operating speed must be at least 20% away from any critical speed (1st, 2nd, or 3rd lateral criticals).

O&M Burden & Strategy

The “Fit and Forget” Myth:

While Westfall mixers are often sold as maintenance-free, they are prone to scaling and ragging. In wastewater applications, struvite or grease can build up on the vanes, altering the K-value.

Strategy: Install differential pressure transmitters across the mixer. A rising Delta-P is an early warning of fouling. Schedule annual inspections via access ports.

Dynamic Mixer Lubrication:

SPX Lightnin gearboxes are robust but unforgiving of poor lubrication.

Strategy: Implement an oil analysis program. Sample gearbox oil every 6 months to check for metal shavings (bearing wear) or moisture ingress. This predictive maintenance is cheaper than a gearbox replacement.

Design Details / Calculations

Accurate sizing prevents energy waste and ensures process compliance. Below are the governing logic and calculations for comparing Westfall Manufacturing vs SPX Lightnin for Mixers: Pros/Cons & Best-Fit Applications.

Sizing Logic & Methodology

1. Determine the G-Value (Velocity Gradient)

The G-value describes the intensity of mixing.

Flash Mixing: $G = 700$ to $1000 text{ sec}^{-1}$ (short duration).

Flocculation: $G = 20$ to $80 text{ sec}^{-1}$ (tapered).

Dynamic Calculation (Camp-Stein):

$$G = sqrt{frac{P}{mu V}}$$

Where:

$P$ = Power input to the water (Watts)

$mu$ = Dynamic viscosity ($Pa cdot s$)

$V$ = Volume of the mixing zone ($m^3$)

2. Calculating Head Loss (Westfall Static)

To verify if a Westfall mixer fits the hydraulic profile, use the head loss equation:

$$h_L = K cdot frac{v^2}{2g}$$

Where:

$K$ = Head loss coefficient (specific to the mixer model, typically 0.9 to 3.0 for standard mixers, but Westfall low-head models can be < 1.0).

$v$ = Fluid velocity ($m/s$).

$g$ = Gravity ($9.81 m/s^2$).

Design Check: Calculate $h_L$ at peak flow. Convert this head loss into equivalent energy cost to compare with the motor HP of a Lightnin mixer.

3. Calculating Power Draw (SPX Lightnin)

For dynamic mixers, power is a function of the impeller characteristics:

$$P = N_p cdot rho cdot N^3 cdot D^5$$

Where:

$N_p$ = Power number (impeller geometry constant, e.g., 0.3 for hydrofoils).

$rho$ = Fluid density ($kg/m^3$).

$N$ = Rotational speed ($rps$).

$D$ = Impeller diameter ($m$).

Design Check: Note the $D^5$ relationship. Small changes in diameter have massive impacts on power. Don’t oversize the impeller “just to be safe.”

Specification Checklist

When writing the RFP, ensure these distinct items are included:

For Westfall (Static):

- CoV Requirement: Specify CoV < 0.05 at X pipe diameters.

- Maximum Head Loss: “Head loss shall not exceed X psi at Y gpm.”

- Injection Ports: Specify number, size, and quill type (retractable vs. fixed).

- Internal finish: Surface roughness ($R_a$) if fouling is a concern.

For SPX Lightnin (Dynamic):

- Service Factor: Minimum 1.5 or 2.0 for gearboxes (AGMA standards).

- L10 Bearing Life: Minimum 100,000 hours.

- Impeller Type: Hydrofoil (A310 style) for flow-controlled blending; Pitch Blade Turbine (PBT) for solids suspension.

- Shaft Design: Calculate and certify critical speeds.

Standards & Compliance

- AWWA C651/C652: Disinfection standards relevant to mixing efficiency.

- NSF/ANSI 61: Mandatory for potable water contact.

- OSHA: Guarding requirements for rotating shafts (Lightnin).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary difference between Westfall and SPX Lightnin mixers?

The primary difference is the source of mixing energy. Westfall Manufacturing produces static mixers that use the fluid’s own velocity and pressure drop to create turbulence via fixed vanes. SPX Lightnin produces dynamic mixers that use electric motors and rotating impellers to actively agitate the fluid. Westfall is best for inline pipeline mixing, while Lightnin is best for tank and basin mixing.

How do I calculate the energy cost of a static mixer?

While static mixers have no motor, they consume energy by resisting flow (head loss). To calculate the annual cost: Calculate the head loss (in feet or meters) at average flow. Convert this head loss into Pump Hydraulic Horsepower (Water HP). Divide by pump/motor efficiency to get Brake Horsepower. Multiply by operating hours and electricity rate. This “phantom load” is often lower than a dynamic mixer’s motor draw but must be evaluated.

Can Westfall static mixers handle wastewater with rags?

Standard twisted-tape or complex vane static mixers can clog in raw wastewater (ragging). However, Westfall offers specific “non-clog” designs (like the Model 2900 or open-vane designs) that allow solids to pass. Engineers must specify the fluid type carefully; putting a potable water mixer design into a wastewater sludge line will result in immediate clogging.

Why would I choose a dynamic mixer if a static mixer is cheaper to maintain?

You choose a dynamic mixer (SPX Lightnin) when the application requires: 1) Mixing in a tank or basin (flocculation, storage). 2) Handling variable flows where the velocity might drop too low for a static mixer to work. 3) Keeping heavy solids in suspension, which requires active energy input independent of throughput. 4) Process flexibility via VFD control.

What is the typical CoV (Coefficient of Variation) target for water treatment?

For chemical flash mixing (coagulants, disinfectants), the industry standard target is a CoV of 0.05 (or 5%) usually measured 5 to 10 pipe diameters downstream of the mixer. This indicates that the chemical concentration varies by no more than 5% across the pipe cross-section, ensuring uniform reaction and minimizing chemical waste.

How much straight pipe does a Westfall mixer require?

Requirements vary by model, but generally, Westfall mixers are designed to reduce space requirements. A typical specification might require 0-2 pipe diameters upstream and 2-5 diameters downstream. This is significantly less than generic static mixers, making them popular for plant retrofits where space is tight.

Conclusion

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Flow Dependency: Westfall (Static) performance relies on flow velocity. Do not use if high turndown results in laminar flow. SPX Lightnin (Dynamic) performance is independent of flow.

- Energy: Compare the “Head Loss Cost” of static mixers against the “Motor Power Cost” of dynamic mixers for TCO analysis.

- Application: Use Westfall for inline flash mixing, chlorination, and ozone. Use Lightnin for flocculation basins, sludge tanks, and solids suspension.

- Maintenance: Static mixers are low-maintenance but hard to inspect (inline). Dynamic mixers require routine mechanical maintenance but offer easier access.

- Space: Static mixers are the only viable choice for buried pipes or crowded galleries.

In the analysis of Westfall Manufacturing vs SPX Lightnin for Mixers: Pros/Cons & Best-Fit Applications, the engineering decision should rarely be based on brand preference alone. It is a decision dictated by hydraulic physics and physical constraints.

Westfall Manufacturing provides the superior solution for inline applications where head loss must be minimized, and space is at a premium. Their capability to deliver high-efficiency mixing with low beta ratios makes them a standard for chemical injection in pressure piping. However, their reliance on fluid momentum makes them vulnerable in systems with extreme flow variability.

SPX Lightnin remains the standard for open-tank applications and scenarios requiring solids suspension or variable energy input. While the operational burden of mechanical seals and gearboxes is higher, the ability to decouple mixing intensity from plant flow rate provides a level of process control that static mixers cannot match.

For the consulting engineer, the best practice is to utilize static technology for the “rapid mix” and disinfection components of the plant to save energy and space, while reserving dynamic technology for flocculation and sludge handling where residence time and active agitation are non-negotiable.